Forget the world — robots are more interested in taking over our wallets. This year, the amount of assets under management by robo-advisers is projected to reach USD 1.4 trillion [1]. By 2025, that figure is expected to double. As the industry evolves and the amount of money pouring towards robo-advisory grows, so should our understanding of three key questions: Who uses robo-advisory? What factors influence its adoption? And might it share more with human advisory than we expect?

Younger vs older

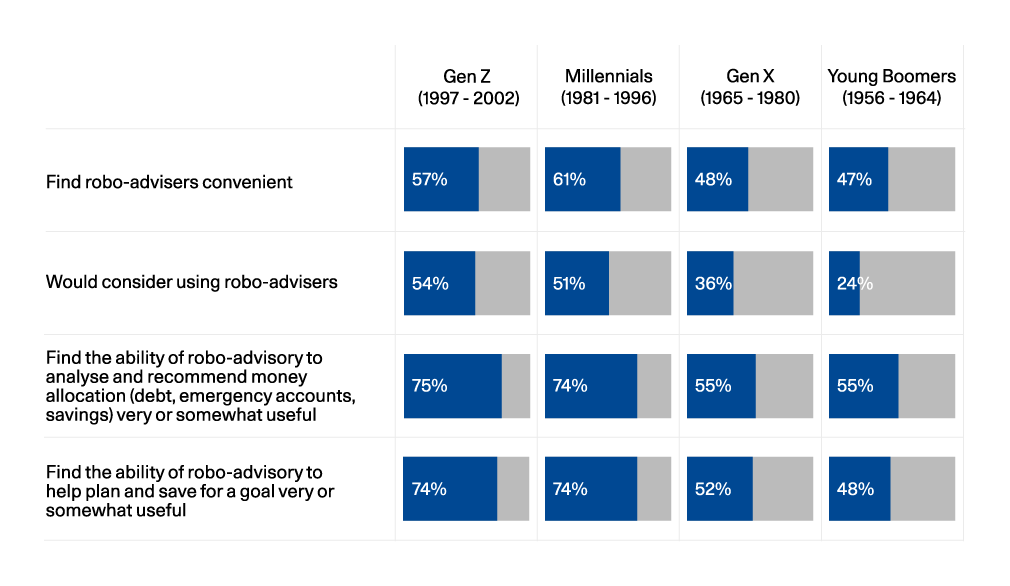

If asked to pick an age group that is most open to using robo-advisory, your answer would probably skew younger — and, according to a 2020 Vanguard study in the US, you would be right. It showed that Gen Z and Millennials would consider using robo-advisers more often than older generations, with a greater percentage deeming them as “convenient” [2]. Indeed, in Avaloq’s own front-to-back office report, we found that 41% of Gen Z and Millennials would be willing to receive fully computer-generated advice [3].

However, do not be so quick to overlook the older generations, even if they present a muddier case. Although they are less likely to consider using robo-advisers, this barrier to adoption does not appear to stem from a lack of esteem for them. In fact, around half the sample in the Vanguard study found a robo-adviser's ability to suggest money allocation or offer support in planning for goals useful.

So, what stops them from turning appreciation into action? That is exactly what organizations looking to attract more clients to their robo-advisory offering may want to explore. Are older generations looking for a more human touch throughout their robo-advisory journey? Is the current solution not as simple to use as a less-than-digitally-savvy client was led to believe? Or is it just that the look and feel of the offering, designed to appeal to younger clients, fails to welcome an older clientele? With some evidence of untapped potential in older generations, firms may want to ensure that they are not inadvertently counting these clients out when designing their robo-advisory offerings and communications.

New vs seasoned investors

Moving on from age, another assumption around robo-advisory has to do with investor maturity, with robos often regarded as starter solutions for first-time investors with little experience and minimal assets. A study in the US begs to differ. The survey of over 5,000 households revealed that, of those who use robo-advisory most, half have USD 500,000 or more in assets [5]. What is more, 45% of people who invest via robo-advisory would classify themselves as “experienced” or “very experienced”, with over half of experienced investors also using a financial adviser. These points serve to position robo-advisory as just another approach to investing and suggest that, while new, small-sum investors might certainly leverage such solutions, they should not be viewed as the defining audience for robo-advisory.

When it comes to segmenting the audience for robo-advisory, instead of creating a dichotomy based on wealth or familiarity with investing, the industry should begin to recognize and integrate other, more attitudinal measures into their thinking. For example, a client’s general affinity for trying new technologies, attitude towards digitalization, or level of comfort with complexity (in this case, of adding another investment approach to their finances) might all shape whether they adopt robo-advisory or not. Best of all, when organizations take these sorts of attitudinal measures into account, they will not just learn more about client views on robo-advisory alone; they will gain a holistic, nuanced understanding of their clients — an understanding that can help shape more client-centric products and communications that truly resonate.

Human vs robot

Conventionally, human advisory and robo-advisory have been pitted against each other. The former is seen as more personable, with a customized approach, but potentially clouded by emotions; the latter is positioned as more efficient and less biased, but lacking a human touch, with some wary of trusting artificial intelligence (AI) with their finances. However, some recent studies are calling elements of this narrative into question.

To begin, the suggestion that people trust AI less than human advisory is not a universal truth. A 2021 study of 11,000 respondents in 11 countries found that cultural attitudes and social factors play a role in whether consumers are likely to adopt AI-based advisory solutions [6]. Where there is a lack of trust or a greater sense of fear of being cheated by human advisers, consumers have a stronger preference for using AI solutions. In other places, where a culture considers social interaction to be important, AI is not as sought after. In both cases, AI adoption does not seem to be influenced as much by the relationship one has with technology, but rather by the relationship one has with other humans around them, with AI, at times, celebrated as more trustworthy.

And the evolution of conversational robo-advisers is only helping build that case. Conversational robo-advisers effectively mimic human-to-human text interactions by engaging in turn-taking or using social cues, such as emojis. When compared to robo-advisers that do not leverage such elements (termed non-conversational), conversational robo-advisers were seen to generate higher levels of trust and more positive evaluations of the advisory process from those investors using them [7].

However, there is a trade-off to equipping robo-advisers with conversational tools: the assumption that the involvement of AI leads to more rational decision-making starts to weaken. In the same study, investors were more likely to increase asset allocation and accept recommended proposals from conversational robo-advisers, even when the proposal was objectively incorrect for their profile. It appears that, when elements of a human-to-human interaction are introduced, so are traces of the very issues that some investors may have turned to robo-advisory to avoid in the first place.

Studies like these encourage us to evolve past the picture of a young, first-time investor, allocating small sums to an impersonal, logical robo-adviser. In reality, the older generation finds certain elements of robo-advisory useful in the same way their younger counterparts do. Experienced, affluent investors leverage such solutions alongside their more inexperienced peers. And AI solutions can elicit trust, generate feelings of engagement and enjoyment, and even guide investors to take irrational financial decisions — just like a human adviser can.

Together, these findings serve as a clear nudge to the industry to leave behind certain dichotomies and form a more nuanced picture of robo-advisory and its users. What with the level of growth still predicted to come in this space, those organizations who do might find themselves at an advantage in the ongoing robo-advisory race.